Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

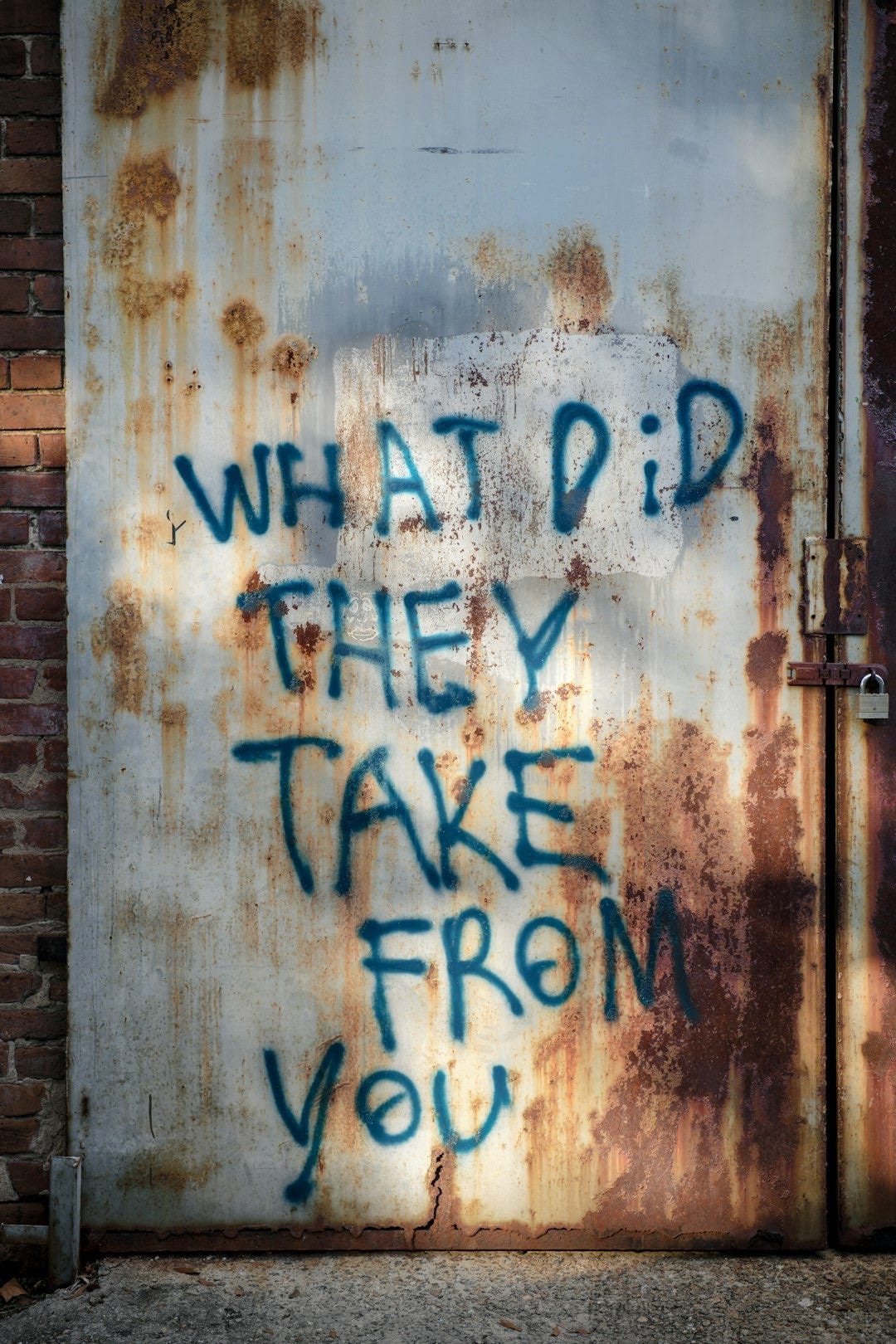

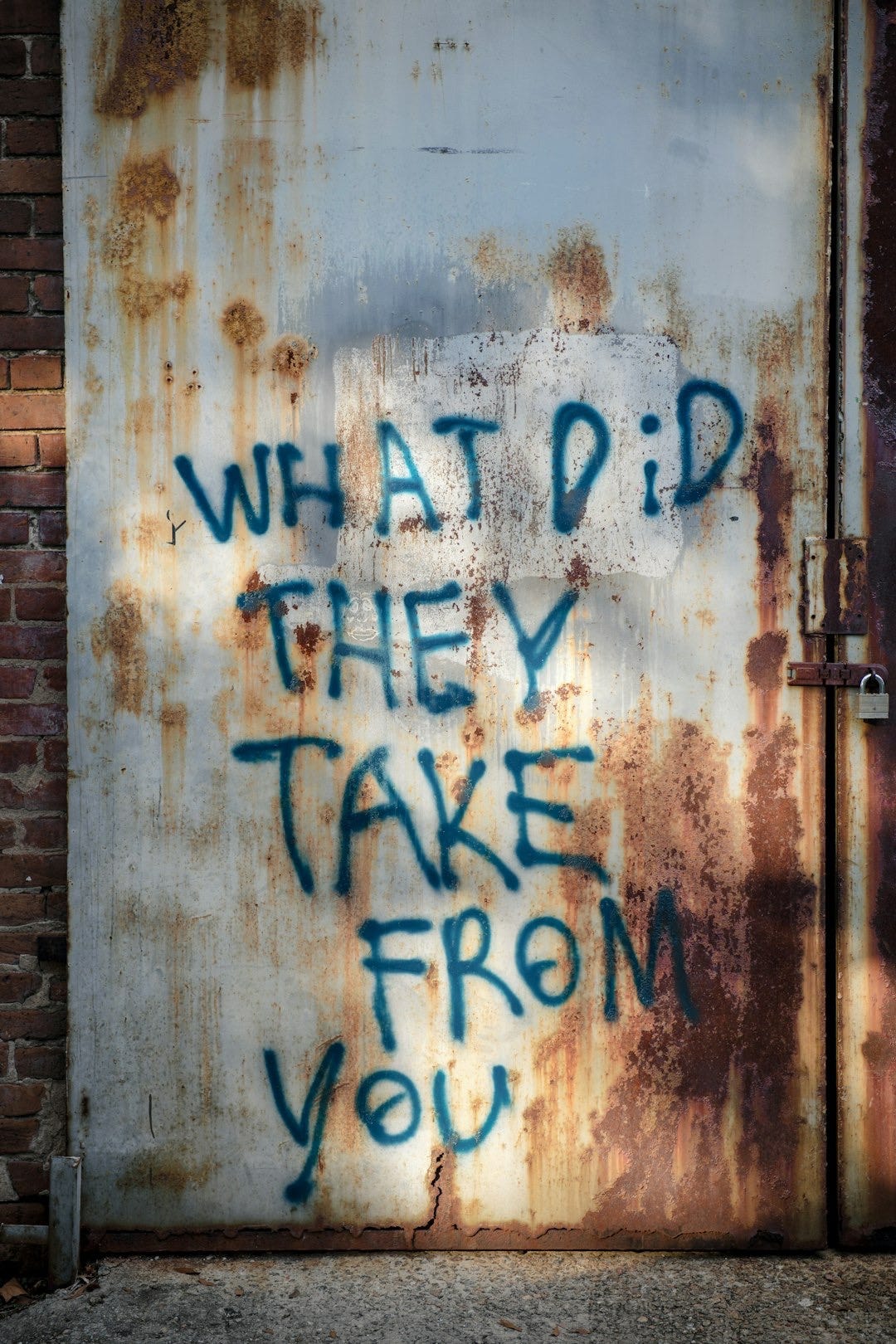

I’ve noticed an influx of parents estranged from their adult children who are turning to TikTok and other platforms to publicly express their grief and confusion. They ask: “Why won’t my child talk to me? What did I do wrong?” These videos are framed to elicit sympathy without accountability. They rarely engage in meaningful self-reflection or name the specific relational harms that led to the cut-off. What I’m seeing on social media from these estranged mothers is emotional bypassing, where the parent seeks validation while continuing to invalidate the adult child’s experience. It is a public-facing reenactment of the dynamics that led to estrangement in the first place.

This is precisely why Mother’s Day becomes a crucible for estranged and conflicted adult children. When these performative displays flood social media they can retraumatize those who have fought hard for psychological safety. These viral pleas are manipulative, and for an estranged or low-contact child, seeing a parent lament their absence publicly is quite literally gaslighting on a public stage.

As a psychologist specializing in trauma and attachment wounds, I want to talk about the plight of emotionally complicated maternal relationships and why Mother’s Day is one of the most emotionally volatile days of the year.

Emotional neglect isn’t just about what was done; it’s about what never happened – recognition, attunement, and emotional safety.

We are conditioned from birth to honor our mothers because motherhood is mythologized as inherently selfless. Our culture expects us to reflexively collude with this fantasy and the narrative that frames every mother as a safe harbor. But for many, that harbor is stormy. Imagine trying to anchor yourself in a place where you are thrashing in the waves, unpredictably and without apology.

The pain is particularly acute for those whose mothers were not just unavailable, but fundamentally misattuned; mothers who failed to reflect their child’s emotional needs and instead related to them as extensions of themselves. In these situations, the child is not seen as a separate person but as an object that functions to preserve the mother’s self-image. Emotional neglect isn’t just about what was done; it’s about what never happened – recognition, attunement, and emotional safety.

For many adult children, whether fully estranged or maintaining strained contact, boundaries represent a radical act of self-preservation. As Agllias (2016) documents in her qualitative study, estranged adult children often cite “persistent emotional abuse, neglect, or boundary violations” as key motivators for going no-contact.

Mother’s Day becomes a crucible for estranged and conflicted adult children.

The psychological toll of estrangement is most acute when cultural rituals demand emotional participation. Mother’s Day serves as a glaring reminder of the bond that should have been. It evokes what some psychologists term “ambiguous loss,” or grief without closure. There is no funeral and no clear ending. There is only silence and pain.

Additionally, for those in low-contact relationships with their mothers, Mother’s Day can become a performance; a forced ritual of reverence where the cost of non-participation is conflict and emotional withdrawal. Many adult children feel trapped in an unspoken bargain: participate in the holiday to preserve peace. The brunch, the card, or the phone call becomes an act of emotional dissonance, where affection is feigned to avoid fallout.

In her work on estranged children, K. Agllias (2018) found that holidays and anniversaries intensified trauma symptoms, including depression, guilt, and intrusive memories. Mother’s Day, then, becomes a day of mourning not just for the mother lost, but for the mother who never truly existed.

Photo by Milada Vigerova on Unsplash

One of the most painful aspects of navigating Mother’s Day with an estranged or difficult maternal relationship is the cultural insistence that healing requires forgiveness or reunion. This is a myth.

Research by Linden and Sillence (2021) showed that estranged adult children often experienced improved psychological well-being, increased authenticity, and relief after cutting ties (See: “I’m finally allowed to be me”, Bristol University Press). For those who remain in strained contact, healing may require emotional distance, clear boundaries, or community validation rather than reconciliation.

Estranged and low-contact children often face judgment and moralization. They are labeled as ungrateful, selfish, or cruel. This stigma compounds the psychological burden and can invite grief and identity confusion. Blake (2017) stresses the importance of reframing estrangement not as a personal failing but as a relational rupture grounded in survival and unmet needs (DOI: 10.1111/jftr.12216).

How to Survive Mother’s Day with a Complicated Maternal Relationship

- Validate your experience. You are not alone. Millions share this pain.

- Create new rituals. Write a letter to your younger self. Burn a symbolic candle. Honor your healing.

- Limit social media. Limit exposure to curated highlight reels and performative posts.

- Connect with your chosen family. Healing happens in relationships that see and respect you.

If you are no-contact or walking the tightrope of a conflicted relationship this Mother’s Day, I see you. The child who protected their own heart when no one else did.

References

Agllias, K. (2016). Disconnection and decision-making: Adult children explain their reasons for estranging from parents. Australian Social Work, 69(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2015.1004355

Agllias, K. (2018). Missing family: The adult child’s experience of parental estrangement. Social Work Education, 37(5), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2017.1326471

Blake, L. (2017). Parents and children who are estranged in adulthood: A review and discussion of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12216

Linden, A. H., & Sillence, E. (2021). “I’m finally allowed to be me”: Parent-child estrangement and psychological wellbeing. Families, Relationships and Societies, 10(2), 325–343. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/frs/10/2/article-p325.xml